Did you ever wonder why, when your make out a check to someone or some business, you have to write in the sum in both numbers and words? If you’re bothered by all those unwanted ads cropping up on your social media, did you ever wish there was no such thing as an algorithm? And, be honest, did you ever wish that you didn’t have to take those required algebra courses back in high school?

All those feelings have occurred to me, but at least now I know who to blame. It’s those clerics and merchants and high-falutin’ academics who prowled the earth more than 1,500 years ago, from Baghdad to Cordoba to Florence and back again.

The Abacus and the Cross, a biography of learned scientist and teacher Gerbert of Aurillac, who ultimately became Pope Sylvester II, shows that the so-called “Dark Ages” weren’t so dark after all. In fact, there was a great deal of learning and trafficking in scientific knowledge going on. Gerbert was a renowned schoolmaster, scientist, and cleric of that era. He intrigued his way to the papacy and got appointed to it by Otto III, the Holy Roman Emperor, in the year 999.

Gerbert’s biography goes into the backstories behind those matters in the first paragraph. It tells of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, which became a veritable research institute around the year 800. It saved for posterity works by such giants as Euclid, Ptolemy, Archimedes, and Aristotle. Much of the scientific know-how from Baghdad eventually made its way to Europe via al-Andalus, the Muslim stronghold in Spain.

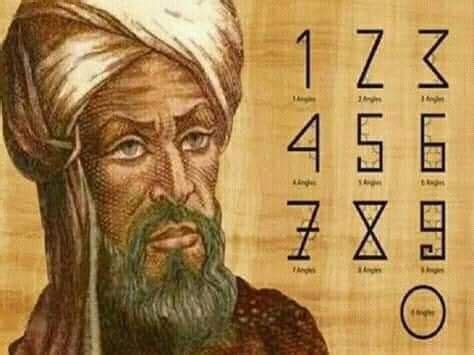

One of the all-star mathematicians from the House of Wisdom was Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who died in 850. He wrote On Indian Calculation, the world’s first book on Arabic numbers – the numbers that ran from 1 to 9 – and the place-value system of working with those numbers. That system originally came from India.

He also wrote The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completing and Balancing. In Arabic, that’s Kitabl al-muktasar fi hisab al-jabar wa’l-muqubalah. That was the first book of modern algebra – or the “al jabar” of the book’s title. But that’s not the last we hear of al-Khwarizmi.

Fast-forward to the career of Gerbert of Aurillac and beyond. Gerbert was an absolute whiz with the abacus, which was the personal computer of its day. For a couple of centuries, monastery schools used the abacus to teach arithmetic. Eventually they evolved from shuffling beads on a counting board to calculating with pen on parchment or with stylus on a wax tablet. They used as a guide a Latin translation of On Indian Calculation by al-Khwarizmi. The Latinized form of his name is “Algorismus.”

So it is that we get both algebra and algorithms from the math whiz of Baghdad.

But as with all evolutions in thought and methods, change was resisted. In 1299, the money changers of Florence, Italy, got into the act. They didn’t trust the Arabic numerals, so they banned the use of “letters of the abacus.” They decreed that no one “dare or allow that he or another write or let write in his account books or ledgers or in any part of it in which he writes debits and credits, anything that is written by means of or in letters of the abacus, but let him write it openly and full by way of letters.”

More than 1,100 years later, we in America still adhere to that proscription – or to some of it, anyway. As I learned when I was a banker-in-training, the Law of Negotiable Instruments states that such an instrument. i.e. a check, must have the amount written out in both numbers and words. If the sums differ, then the verbal one is the official amount.

Now you know the rest of the story.

Tags: al-Khwarizmi, algebra, algorithms, Baghdad, negotiable instruments, Pope Sylvester II

Leave a comment