Presidents and potentates, generals and warlords, captains of industry and show-business celebrities – we chronicle and study their lives. Their deeds – and their misdeeds – are the Cliff’s Notes stories of our civilization. We are supposed to know those stories so that we may make sense of the world we live in.

But it’s not enough to read about those with the big jobs, impressive titles, and bottomless bank accounts. Not if we want to learn the possibilities of the human spirit, to hear of the heights of personal accomplishment, to grasp the boundless potential of human love and sacrifice. Not if we want to understand what it means to be an American.

To comprehend and appreciate such possibilities, heights, and potential, we must know the people who have been there. They’re not in the pages of the history books. But they are all around us, and always have been. I would like you to meet one such man. His name is George Lermond.

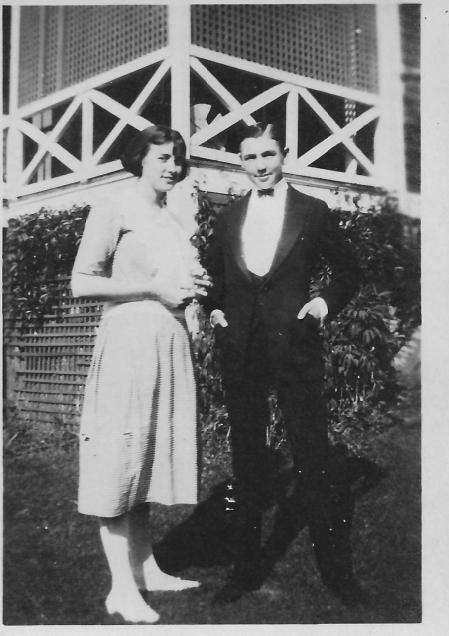

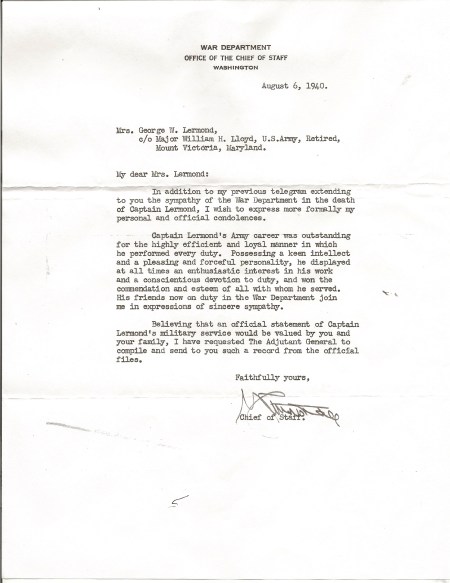

George was born into a poor Massachusetts family. He was a hard-working student, loving son and brother, altar boy, Olympic athlete, soldier, and father. His life touched many of those whom history considers great men.Dwight Eisenhower promoted George Lermond to captain in the U.S. Army. Franklin Roosevelt called on him when he needed trained pilots to fly U.S. air mail. George Patton was to be his next immediate superior before his tragic death in a house fire. George Marshall commended his exemplary service in a personal letter to his family. Roosevelt directed that Lermond and his son, George Junior, be buried together in Arlington National Cemetery.

George Lermond commuted from Nahant to Boston College High School. He graduated from there in 1921 and from Boston College in 1925. He was a superb track athlete, the only one from his college squad chosen to compete in the 1924 Olympics. After BC, he went to West Point and graduated in 1930. I researched and wrote his biography for his induction to the BC Hall of Fame in early October. The full text of the story appears below, along with some photos and letters that I received from family members.

George’s son Bill journeyed from Maryland for the Hall of Fame induction ceremony. His heartfelt words of thanks, as he accepted the bronze plaque for the father he hardly knew, brought tears to many eyes that evening.

Bill, his sister Edith, and his mother Edith, were saved from the blaze that took George Lermond’s life. George lowered the two children, who were wrapped in a blanket, from a window to his wife on the veranda. George then went back inside to save the third child, and perished.

I want the world to know of this man’s exemplary life. Perhaps history won’t number him among the greatest of men. But I do, and I suspect you will agree.

In this our time, it is all too easy to become distressed at the sight of so many charlatans, mountebanks, and outright villains who occupy positions of power and prestige. Do not be distressed. They will be gone and forgotten.

To my fellow baby boomers, who’ve reaped our blessed land’s bounty that was sown by our fathers and grandfathers, I say take heart. The generation of our children, and soon enough, their children, has its own ample supply of George Lermonds. They’ll soon be in charge.

You made them and set them on their way. Have faith.

George Lermond

Boston College High School ’21, Boston College ’25, United States Military Academy ‘30

A middle distance runner and winner of innumerable races and championships during his time at Boston College, Lermond was the only Eagle who made the 1924 Olympic team.

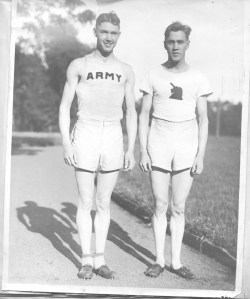

After Boston College he enrolled at West Point and graduated in 1930 while continuing his track career and grooming his younger brother Leo to track stardom.

George was a championship-caliber runner well into the 1930s while serving in the United States Army. He died tragically in a house fire in1940, on the eve of World War II.

George Lermond was the prototypical student for whom Boston College was founded. The third child in a poor but hard-working Catholic family, George was born in Revere, Massachusetts. His father left when he was ten years old, and his mother Julia Lenehan Lermond moved to Nahant to be with her parents.

George’s uncle, Father Daniel Lenehan, was pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Malden. A frequent visitor to the house, he undoubtedly had something to do with George’s enrolling at Boston College High School in Boston’s South End. George commuted the 15 miles every day. Like many BC High lads, he then proceeded right to Boston College.

“Lemons” fit right in with the other Eagle track stars. He was on the distance medley team with Tom Cavanaugh, Luke McCloskey, and Louis Welch. They won four national championships and broke three world records.

George was the New England two-mile champion three straight years, and in one of those victories he set a course record of 9:33.5. Sportswriters called him “the sensation of the Eastern track world” in 1924. Among his many victories were the Millrose Three Mile in New York, the New England Two Mile championship, both indoor and outdoor, the National AAU 5- Mile, and the BAA Games Two Mile.

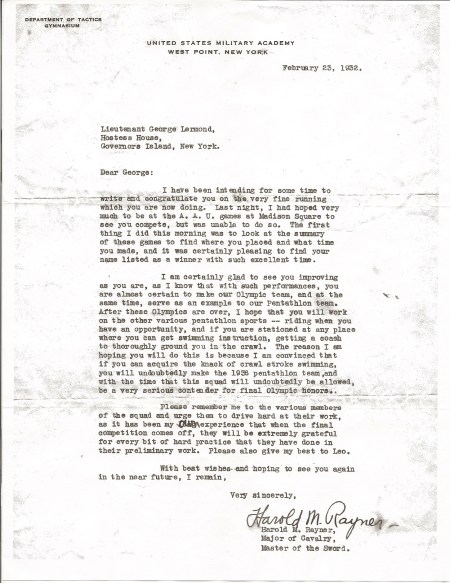

At the Paris Olympics George faced the immortal Paavo Nurmi and his mates from Finland in the 5000-meter run. Nurmi won the gold and George finished 24th. Aged 19, George was the second-youngest American ever to compete in the 5000.Returning to Boston after the Olympics, George was the AAU six-mile champion in 1925. In January of 1925, he placed fourth against Nurmi in the 5000 at the Millrose Games in Madison Square Garden.

George also ran for the Boston Athletic Association. He introduced his younger brother Leo to Jack Ryder and the BAA. Under Ryder’s direction Leo became as big a star as George. Leo finished fourth in the 5000 at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam.

George and Leo also ran for the New York Athletic Club during the 1920’s, and press reports speculated that the United States would have two brothers competing at the Amsterdam Olympics in the 5000. George was at the peak of his powers at the time, holding the Military Academy records for the half-mile, the mile, and the two-mile. But he came up short during the trials, probably wearied from competing in multiple events at West Point.Service to the county was in George’s family history. His grandfather Patrick had lied about his age to get into the 55th Massachusetts Infantry in the Civil War. A great-grandfather, William McCallister, served at both Petersburg and Appomattox.

George’s first military career stop was at the Air Corps Flying School in California. Though commissioned as a flyer, he stayed with the infantry. However, he was one of 262 Army pilots who delivered the nation’s air mail for 78 days in 1934.

George returned to an infantry assignment at Fort Jay on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor. He kept running and aimed for the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles. His personal bests in several events took place around that time. In 1930 he posed a 1:55.3 in the 880 and a 4:15.2 in the mile. In 1932, he ran the two-mile in 9:16.6. It was also in 1932 that he set the unofficial world record for the 3000 meter steeplechase at the Eastern Olympic Tryouts at Harvard, with a time of 9:08 2/3.He and Leo competed in a track meet in Lynn before the national Olympic tryouts, and George injured an ankle going over a water jump and missed the national final tryouts. The winner was Joe McCluskey, with a time of 9:14.8, much slower than George. McCluskey ended up taking the bronze in Los Angeles.

George did go to Los Angeles in 1932, however. He was a coach in the pentathlon. That event, consisting of fencing, swimming, show jumping, pistol shooting, and a distance run, was a showcase for military competitors. Richard Mayo won America’s first-ever pentathlon medal, a bronze.

George attended chemical warfare school in Maryland in 1934. After a graduate course in infantry at Fort Benning, Georgia, he was assigned to the 15th Infantry Brigade in Tientsin, China in 1936. His wife Edith accompanied him.

Japan invaded China in 1937, and the 15th ‘was reassigned to Fort Lewis, Washington. George’s immediate superior was and up-and-coming colonel named Dwight Eisenhower. Ike promoted George to captain in 1940.

George Lermond’s final assignment was to tank school at Fort Benning. He was slated to train under General George Patton, but he never got there. He and his family stopped for a few days at the luxurious Mount Victoria in LaPlata, Maryland, while Edith’s parents took a short vacation.

On the night of July 5, a fire broke out in the upper floors and spread quickly. George was able to lower Edith, four-year old Bill, and 15-month old daughter Edith to a porch by using a bedsheet. He dashed back into the house to save George junior and was overcome by the smoke. He was 35 years old. President Roosevelt directed that he be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.