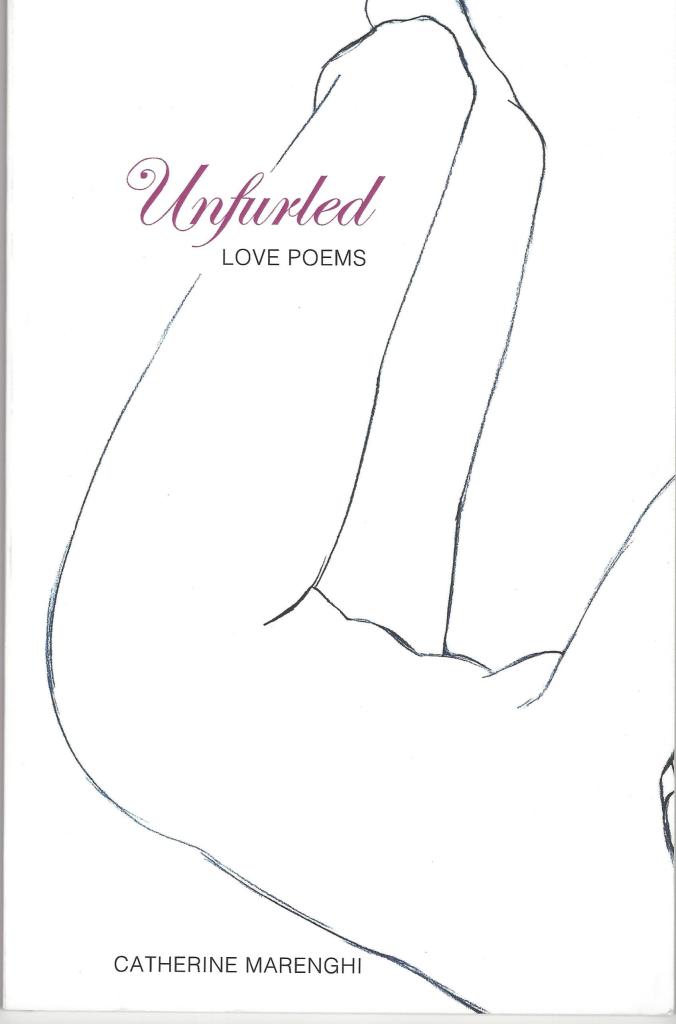

Women who read the love poems of Unfurled, Catherine Marenghi’s latest book, will close the book, sigh, and smile knowingly. They’ve been there.

Men who read the love poems of Unfurled will close the book, sigh, and smile wistfully. They wish they could go there.

Both women and men will close the book, sigh, and reach for the nightstand. Instinctively. They’ve got an overwhelming urge for a cigarette.

Who wouldn’t crave a smoke after surfacing from a plunge into Ms Marenghi’s erotic oeuvre? Here’s just a taste:

In Having You:

I could tell you that I miss

Those predawn hours, my skin

Nesting into yours, feeling

That familiar nudge

My body opening its eyes

In sweet recognition.

In Upon Being Kissed by a Man for the First Time in Seven Years:

I want to inhale him into my mouth,

let him liquefy on my tongue

like confectioners’ sugar—

In Certainty:

But then you meet a man

and now a shared cup of coffee steams

like a tango on a Mexican dance floor.

One look from him is enough

to clamp you like strong thighs.

And words and tears flow equally,

without fear or shame.

Oh, yeah. Gimme another cigarette.

But wait. This wonderful collection of 37 poems is not a book of erotica. There’s joyful sex aplenty, but The Joy of Sex it isn’t. So if I gave you the wrong impression, I apologize.

This is a book about love. That’s why its subtitle is Love Poems and not Provocative Poetry. It’s not just about the carnal love of woman for man, and vice versa. Rather, it’s a rapt immersion in love’s nearly bottomless, untamable emotions, both blissful and painful.

As William Wordsworth wrote in The Prelude, “words can give, / A substance and a life to what I feel.” Ms Marenghi takes her readers by the hand and, with her felicitous diction and her gift for well-turned metaphor, tells us what she felt and what we undoubtedly felt as well, in the delight and passion of our own experiences of love in all its forms.

The first time I read through Unfurled, I thought of The Bible. I wrote a little blurb that I think came close to the mark. I’ll stick with it here:

“Bible scholars say that The Song of Songs presents an inspired portrayal of human love and a resounding affirmation of the goodness of human sexuality. With her love poetry, Catherine Marenghi re-affirms all that goodness for us and proves herself a worthy successor to King Solomon.”

The above is true, but I’ll also say that she goes Solomon one better. Because there’s much more than the erotic, the sexual, in these pages. The old king never wrote about a cherished little brother and the heartbreaking lesson in life he imparted at the age of eight before his tragic death a year later, as Ms Marenghi tell us in The Only Question:

He seemed to know

how little time there was

His ninth birthday, already

choked with pneumonia, he was

swallowing his own death

Nor did Solomon ever anthropomorphize his original temple and tell us how it felt before he built that grand new one. But Ms Marenghi’s award-winning poem The Affair does that; her old house, realizing she’s being abandoned for a new house in a warmer clime,

“began to will herself

to rot at her sills,

clench her roof shingles

till they swallowed the rain

and stained her plaster ceilings.

You will pay for this, she said,

No one will want me now.”

And here’s one that gave a chuckle to a few ladies I know. Solomon never had any need to use a dating app, but apparently Ms Marenghi did. In Bio for Match.com, after describing several gritty and unattractive details about where she lives, she continues

Shall we tell the boys that?

It would be more biographical than

Her favorite song, favorite book,

Favorite film, whether she’s Catholic,

Jewish, “spiritual but not religious.”

To every question, she replies,

None of the above.

There was even a hint of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sharp elbows and give-no-quarter attitude in Forgiveness; breaking up a disappointing relationship, she declares

This will be a kindness shown

to me, and not to you.

I unwrap this tightness that

had bound me to you.

Notwithstanding all the above excerpts and selections, I don’t want this post to be merely a book review. I’d like to say a bit about Catherine Marenghi, storyteller and poetry reader, as well. Back in April, which was National Poetry Month, she gave a reading and talk in her native town of Milford, Massachusetts. It was in a library, just across the street from the junior high school where a young substitute teacher named Mrs. Robbins launched Ms Marenghi into her career as a poet. And she did it with a single word: “Wow!”

The author opened the reading with a yet-unpublished poem dedicated to that teacher. For me, it was the most touchingly poignant moment of the entire evening. “Wow! You can write!” was the teacher’s comment on a poetry assignment. The children in the class, but most especially Catherine Marenghi, loved Mrs. Robbins. They thrilled to how she respected them, encouraged them, and made them feel about themselves and their work. But tragically, that beloved teacher ended her own life by suicide a few years later. No one knows why. But I couldn’t help thinking…if only she had felt the love that all of her students had for her. If only she could have heard the poem that I heard, the one dedicated to her by her most accomplished and most loving student of all.

Love and emotion, indeed.

We heard yet more varieties of love – or, more precisely, of loving feelings in other contexts – in readings from her earlier book, Breaking Bread. There was her motherly love for her only son; first, as he entered kindergarten, and then many years later, as he prepared to move across the country to begin graduate school in a distant state. Then there was the almost elegiac feeling of love during a visit to her own elderly mother, nursing-home bound and already cloaked in the mists of dementia.

Both in her reading that night, and in the post-script to the book, Ms Marenghi mentioned her not-so-hidden agenda: to combat the insidious and ubiquitous prejudice of ageism. “As a woman of my late sixties as of this writing, I have been pleasantly surprised to discover that the capacity for love – including physical, erotic love — does not diminish with age.”

We who are of that age group undoubtedly concur and appreciate that, especially after reading and pondering What Remains of the Light, the second-to-last poem in the book.

We all need poets and poetry. As Robin Williams, in his role as John Keating in Dead Poets Society, puts it, “We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion.”

We also need poets to be our guides, sharing their intensely private and personal experiences in order to connect us with what we may have felt but did not really understand and could not yet articulate. I can’t think of a more reliable guide through the realm of human love than Catherine Marenghi.

And as for Unfurled, I recommend it unreservedly. Savor it. Re-read it. Keep it on your nightstand. Right next to that pack of cigarettes.