Tom “Red” Martin, one of Boston College Hockey’s All-Time Greats, Passed Away on July 27, 2017. I’ve known Tom for many years and have frequently interviewed him for articles and books. This blog post has two pieces I wrote about him: a profile in the 2014 Beanpot Tournament program, and a chapter section from Tales from the Boston College Hockey Locker Room.

Rest in peace, Tom. They’ve broken the mold. We won’t see your like again.

From the Beanpot Program

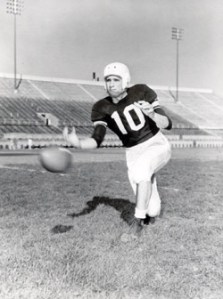

Tom Martin: Just a Hard-Working Kid from North Cambridge

By Tom Burke

In the Land of Beanpot, it is a truth universally acknowledged that Tom “Red” Martin played the entire 60 minutes of Boston College’s 4-2 championship win over Harvard in 1961. True, though Martin sat out two minutes of action for a minor penalty.

That feat wasn’t such a big deal for Tom. After all, he usually logged more than 50 minutes per game anyway. He’s prouder that he scored the winning goal, taking Billy Hogan’s faceoff draw at the point and letting fly a slap shot that caught the inside of the far post.

Defeating Harvard in that Beanpot final was the last big triumph for BC in Martin’s college career, which included two All-America accolades and the Walter Brown Award. But maybe it shouldn’t have ended that way. Watson Rink at Harvard was Tom Martin’s early hockey home, and he probably should have gone to play for Cooney Weiland. He initially decided to do so, but Eagle coach John ‘Snooks” Kelley won him over with “Your mother would want you to go to Boston College.”

Tom’s mother Anne was a marvelous, hard-working lady who waited tables in and around Harvard Square. Widowed when Tom was two years old, she moved into a house owned by Saint Peter’s Parish and frequently needed “Mother’s Aid” charitable payments to make ends meet. One time, when Tom had sneaked out for a football practice before he’d done his chores, Mrs. Martin walked to the field and marched her son off the gridiron and back home.

That never happened again, and Tom had already developed his own work ethic anyway. From age eight through college, he sold papers at the Sunday masses at St. Peter’s. He would help Tom Sheehy, the manager of Watson Rink, scrape the ice and wet it down with water from wooden barrels.

Mr. Sheehy let Tom skate there frequently. Sometimes he’d go one-on-one with Billy Cleary. On other occasions he scrimmaged with the Harvard varsity at practices. When he had Watson’s ice sheet to himself, he’d practice skating backwards. Then he would run the two miles to home backwards, pivoting sharply each side as he went.

Tom played baseball and football in high school and states that learning to take and deliver hits in football was an invaluable preparation for hockey. Jimmy Fitzgerald, who scored the winning goal for BC in its 1949 NCAA championship win over Dartmouth, was his high school coach and first hockey mentor.

“I learned the fundamentals of hockey from Jimmy,” said Tom. “Things like getting out of the zone, head-manning the puck and breaking out yourself after you’ve passed it. That way you create an opportunity for yourself. He also taught me the basics of passing.”

After college, Martin started out at Boston University Law School. He left after a semester, however, because he wanted to join the U.S. National Hockey Team and eventually play in the Olympics. He made the 1962 team that took a bronze medal in the World Tournament in Colorado Springs.

Back home, Martin needed to work before Olympic tryouts. He took the suggestion of BC accounting professor Jim Dunn that he join one of the Big Eight accounting firms, known as “Ulcer Outfits” for the pressures they put on workers.

Tom landed a job at Arthur Andersen and was assigned audit work at Perini Construction in Framingham. Tom got the leeway to work on his hockey game in the mornings and come in to work around noon. He was the only “cake eater,” as western-based players called eastern boys, to make the final cut. He became assistant captain of the team and roomed with Herb Brooks for the 1964 games in Innsbruck, Austria.

Boston College fans of that era fondly recall Martin’s long floater-play passes to classmate Billy Daley that frequently resulted in scores. Daley would win a defensive zone faceoff and bolt straight up ice. Martin would swing the net, wait for opposing defenders to yield a passing lane, and hit Daley in full stride near the center circle.

When opponents adjusted, Tom found a different gap in the coverage or banked the puck off the boards. He got the same results – from assessing the situation, taking advantage of openings, exploiting opportunities, and making adjustments.

That modus operandi might well be the story of Tom Martin’s business life. On several occasions he has recognized business opportunities or detected developing trends in the marketplace, and he’s moved to take advantage of them – just as he did with pinpoint passes through gaps in hockey defenses.

Tom’s Norwood-based company, Cramer Productions, is one of the most highly respected integrated marketing communications organizations in the country. Cramer employs over 100 people in event planning and executions, video and digital production, interactive media, web casting, and print and direct marketing. The company’s revenue tops $30 million per year. Its client roster includes EMC, Fidelity, Jordan’s Furniture, Raytheon, Reebok, Ocean Spray, Michelin, Motorola, and many other big names of the business world.

Tom went back to Andersen after the Olympics and stayed there for five years. He also made time to serve as Snooks Kelley’s assistant at BC for three years, earning a whopping $500 salary. He then accepted an offer from his greatest career mentor, Tim Cronin, who ran Cramer Electronics. Like Cronin, who was fifteen years his senior, Tom was trained as a numbers guy. But he learned all about management and leadership from watching Cronin deal with people.

Cramer grew to national size and more than $100 million in sales. Tom was put in charge of the Northeast region. After Arrow Electronics purchased Cramer in 1979, Tom saw an opportunity and took out a loan to buy the company’s small video equipment division. He’d noticed that Japanese companies had been promoting video, then a new business technology, for businesses communications. Arrow wasn’t interested in video.

Tom kept the Cramer name and launched Cramer Productions. After a few years, he noticed that many of his clients weren’t getting full benefit from the video equipment. At meetings, they still used boring slides and overheads.

“I thought ‘Hey, we should be in the production business’ and our clients liked the idea. So we set up a studio in our building in 1982 and did a few automobile commercials. Car commercials were all produced locally in those days,” he said.

Somewhere along the way, Barry and Elliott Tatelman of Jordan’s Furniture came calling. Cramer began producing all of the popular “Barry and Elliott” commercials. Word got around, and Cramer Productions outgrew its Newton location. They moved to bigger quarters in Braintree.

The high inflation of the mid ‘80s nearly put the Cramer under as the prime rate soared from five percent to near 20 percent. Technology kept changing in the capital-intensive production business, requiring smaller film, more compact cameras, and differently configured editing suites. “We were hanging on by our thumbs,” says Tom.

But he saw another opportunity amid the difficulties. The company meeting planners needed video for their events. Cramer began renting out its equipment and added creative services and event staging to the product line. Business flourished again, and soon Cramer needed bigger space.

Tom got another loan, this time for a million dollars, and bought a 70,000 square-foot building in Norwood. Cramer worked hard to build up the meeting planning and event production business while burnishing their reputation in film production.

Sports fans will recognize several Cramer film oeuvres: “Banner Years,” the Boston Garden farewell; “Boston Red Sox: 100 Years of Baseball History;” “The Story of Golf,” an Emmy-winning PBS feature; and “The Beanpot: The First 50 Years.”

About ten years ago came another sea change. The digital marketplace was taking off. Information would be transmitted digitally – over the Web and on CDs – and Crammer staffed up to get in on the action. Martin went out and hired, and digital is now a big segment of Cramer’s business.

Tom keeps a financial information binder in his office. Not everybody gets to see its color-coded graphs and charts that tell the Cramer business score and standings from every conceivable angle. His accounting background at Andersen drilled fiscal discipline into him. He had seen many businesses and some competitors close up shop after neglecting to manage the balance sheet.

There’s another binder that every visitor to the company can see, however. It bulges with dozens of thank-you letters from charitable organizations that Cramer has helped over the years, either gratis or for cost. The senders include Big Brother/Big Sister, Bridge Over Troubled Water, Easter Seals, Franciscan Children’s Hospital, Greater Boston Food Bank, Jewish Community Housing for the Elderly, March of Dimes, Mother Caroline Academy, Sisters of Saint Joseph. Rosie’s Place, and Second Helping. Cramer dispenses at least a million dollars’ worth of professional services to non-profits each year.

Tom and his wife June celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2012. Six of their seven children are on the Cramer Productions team. Tom is company chairman and the face of Cramer, but much more active on the golf links nowadays. And he’s good at that too. He has won the senior division of the Ouimet Memorial Tournament and the Massachusetts Senior Amateur Championship.

A favorite quote from Danny Thomas in Tom’s office gives a visitor yet another clue to Tom “Red” Martin’s career. “Success in life has nothing to do with what you gain in life or accomplish for yourself. It’s what you do for others.”

Excerpted from the Beanpot chapter in Tales from the Boston College Hockey Locker Room: A Collection of the Greatest Eagles Hockey Stories Ever Told by Tom Burke and Reid Oslin

One old and familiar bit of Beanpot lore is defenseman Tom “Red” Martin’s playing the entire game of the 1961 championship final and taking home the Most Valuable Player Award. True, but with an asterisk. Martin had a minor penalty in the game, so he skated for 58 minutes, not 60.

Tom was a three sport athlete who always kept himself in fine shape. He also played first base for the Eagles’ baseball team that made it to the College World Series in 1960 and 1961. He routinely played 50 minutes a game anyway. It was more difficult in the packed and hot Boston Garden than in chilly little college rinks, but hardly a superhuman feat for Red Martin.

Tom is prouder of scoring the winning goal than he was of playing at much as he did that evening.

“Billy Hogan drew back a faceoff to me. I was a right-handed shot. A kid from Harvard came out to block it, and my shot caught the left inside post,” said Tom.

That was BC’s third goal, scored at 10:06 of the third period. The Crimson got one back to narrow the margin to a single goal again. Martin’s classmate Billy Daley scored on a wraparound to clinch the win with 2:29 to play. Hogan had opened the scoring in the first period and assisted on Jack Leetch’s second period goal. Jim Logue made 30 saves in the BC net to just 17 for Harvard goalie Bob Bland.

It was the first time that attendance in the old Boston Garden hit the magic number of 13,909, a capacity crowd and the largest to witness a college game there since 1931.

Snooks Kelley waxed particularly eloquent after the game. He said afterwards,

“I’ve said I thought we were the best team in New England, even when we lost a couple. But now I know we are the best in the East. Of that I feel positive. That Jimmy Logue is the best goalie in the business. Look what he did tonight. Red Martin is as good a defenseman as anybody will ever find. Billy Daley is terrific. Those sophomores – Billy Hogan, Ed Sullivan, Jack Callahan, Jack Leetch, Ken Giles and the rest. Tonight they were wonderful. They wouldn’t be denied.

“You can stop a Daley two times. He’ll get in the third time. You knew Red Martin would come through. Men like these can’t be stopped forever. And they weren’t.”

Snooks might have gotten a little carried away in his euphoria. Harvard had beaten the Eagles twice already and was missing three of its regulars in the Beanpot. They didn’t lose another game and finished 18-4-2 to BC’s 19-5-1. Tom Martin, looking back on it all, says simply “It was a great rivalry.”

Few people of that era appreciated the BC-Harvard rivalry as did Tom Martin. He grew up in North Cambridge and spent many hours skating and scrimmaging one on one with a student named Bill Cleary on the near-perfect ice surface at the Crimson’s Watson Rink. He played high school hockey at Cambridge Latin under Jimmy Fitzgerald, scorer of the winning goal in BC’s 1949 NCAA championship game against Dartmouth.

Martin initially decided to play his college hockey for Cooney Weiland at Harvard. He informed Fitzgerald, who asked him to go and let Mr. Kelley know. That Mr. Kelley was Snooks, who taught in the school. Young Martin dutifully told Mr. Kelley, who promptly summoned a substitute to monitor his class. He brought Martin to the teacher’s lounge and laid the full Catholic trip on the lad, finishing his pitch with, “And your mother would want you to go to Boston College.”

Whether Tom’s mother Anne ever had a preference for Tom’s post-secondary schooling, we’ll never know. But the Catholic angle hit home with Tom. Anne, widowed when Tom was two, lived in a house owned by Saint Peter’s Parish. Tom sold newspapers at Sunday masses from the time he was in the third grade until after college. Even though he lived about a mile from Harvard, he was going to BC.

He and Daley made the floater play a staple of the BC attack. They liked to pull it late in the game, to “send ‘em home happy” as the wisecracking center Daley would say in calling for the floater. Daley would win a defensive zone draw back to Martin. Tom would retreat behind the net and watch as the opposing defensemen moved laterally out on the blue line. Daley would then sprint up the ice, his diagonal path taking him through the gap between the defensemen. Martin, emerging from the other side of the cage, would then hit the streaking Daley with a long pass and send him in alone for the score.

The floater play worked many times, with Billy Daley getting the goal and Tom Martin the assist. But in the 1961 Beanpot it was Tom Martin who scored the crucial goal. He never came off the ice, save for the two minutes of his penalty, and the 13,909 who were there that evening saw a feat of endurance that has never since been duplicated, and almost certainly never will.