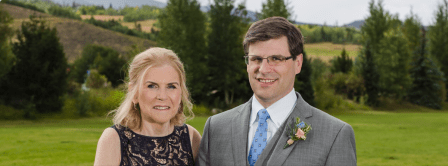

Mary Ellen Burke and her son Matthew on his wedding day.

This was posted on my son Matthew’s Facebook page on December 19, 2019, two days after Mary Ellen passed away. I was pleased to learn, a few days later, that he had read it to her during one of his visits to the nursing home a couple of months before her death.

Telling Her Story: To My Mother

Matt Burke·Thursday, December 19, 2019

The last number of the musical “Hamilton” is a choral ballad called “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story.” And as this musical came to prominence in the popular consciousness — and, indeed, in my own — just as this vile Alzheimer’s disease was taking hold of my mother, the last few years have granted me a lengthy opportunity to ruminate precisely on these questions. When she passed, who would tell her story? And what would that story be?

First let’s explore what that story is.

I’ll remember a number of qualities about my mother. Today I want to emphasize four: curiosity, independence, levity, and gratitude.

First, curiosity: my mother’s true avocation was teaching. She taught every grade from first to fifth, and even in the “off-season” never missed a chance to instruct us on something. While many of our friends took vacations to the beaches of Cape Cod and Maine, you could find us at Colonial Williamsburg or Washington, DC. Even for day trips, we had our excursions to the Freedom Trail, Plimoth Plantation, Sturbridge Village. We had our yearly memberships to the Museum of Science and the Aquarium, and took great pleasure breezing into the exhibits like we owned the place. But it wasn’t just the academics she taught us about. From the Shawn Halloran and Mike Power years, Andrew and I sat with her in the stands at BC football games while Dad was in the press box. And she was the one who taught us how football worked. Who the players were. What a pass, a run, a first down, and a tackle were. So when friends asked Andrew and me how we knew so much about football, we’d waste no time in saying “My Dad is the BC football announcer!” and she would never fail to add “… while you were sitting in the stands with your mom!” She taught us to ask questions about what was around us, to want to know why things were the way they were — and, most importantly, for us to want to keep learning. To be curious.

Next, independence. Part of teaching Andrew, Emily, and me about the world was to let us be our own people. The most poignant example was in March 1997, when I greeted her with a letter of my acceptance to the Congress-Bundestag Program, and that I’d been invited to spend a year in Germany. What I didn’t learn until much, much later was that, that evening, she went and collapsed in tears on the neighbors’ couch. And yet despite the exorbitant sacrifice of not seeing her oldest child for a year, she let me do it. It was my choice, and she let me make it. And 22 years on, I still recall it as the most transformative experience of my life.

Two years later, I played my last hockey game at Boston Latin. We were bounced from the state tournament at UMass-Boston, and I was down on myself about my lack of playing time. And as we were in the foyer of the rink, getting ready to go home, one of the biggest supporters of my athletic endeavors turned to me, saw the melancholy expression on my face, and said “You know, Matt… This is the biggest thing some of these kids are ever going to do.” Of course we had better things to come. So go and do them.

Next, levity. While my mother was often serious, she possessed some Truly. Legendary. Sass. I remember once, in the summer of 1994, she came back from an errand at CVS, where she met a perfectly coiffed political neophyte campaigning for the United States Senate. His name was Mitt Romney. Now, I knew Mitt from his commercials, so was somewhat dumbstruck that my mother would get to shake hands with a famous person. “You got to meet Mitt Romney!?!” I exclaimed. And without a moment’s hesitation, she shot back “Pshhh, he got to meet me!” Or there was the time in late 2011, when I told her after a few dates with Jenny that I’d started seeing someone. Her first question, “Oh really? A girl?”

And as great as she could dole it out, she could take it. Andrew, Emily, and I always loved to ask her how she knew so many people named Mr. So-and-so, or why she had friends named Joe and Mary Biscuit. Or that we never allowed her to forget that one Christmas when she didn’t wrap gifts – or, as she penned it into family lore, the year the elves went on strike. And in all of this, she taught us that there is always levity. And that you can laugh, and be happy.

Lastly, gratitude. Mom always taught us to be thankful for what we had, rather than complain about what we didn’t. She taught us to always say “thank you,” and to look the person in the eye when you did. And had she not taught us this, it would have been very easy, over these last few years, to grow bitter that an incurable, odious brain malady was gradually taking my mother. But she taught us always to be grateful, so I’ll be grateful for the 38 years I had, not the 10 or 15 extra that I might have.

I’m grateful that I was able to dance with her at my wedding. For our trip to Ireland in July of 2017. As her condition really accelerated over the next year, I told friends that I just wanted her to live to see Hannah born. Well, she was at the hospital when Hannah was born. She held her, and saw her several more times over the coming year. While I might not have her to lean on as I raise my child, I do have her example. Even this June, when she was deteriorating rapidly, I showed her some videos of her only granddaughter learning to stand. “Oh, that’s cute,” she said.

I’ll always remember one of our last interactions as one in which my daughter brought her joy.

In the spirit of gratitude, therefore, we would be remiss if we didn’t thank everyone who helped us along this path.

- To our friends and family, thank you for your support, and for lending an ear and extending your kind words. In times of loss and imminent loss, kindness from those who live reminds us of whom we have left to be grateful for.

- To mom’s doctors and caregivers. We are grateful for the support you lent us, the explanations you gave to us, and everything you tried.

- To Mom’s family. Her siblings, their spouses, and many of the Hughes cousins who dropped in to lend a hand or a condolence. And Christine, thank you for being a confidante, advocate, and explainer-in-chief. We could not have managed our way through this without you.

- To my wife, Jenny, and our daughter Hannah. Thank you for your support, and your understanding, particularly during these last few months when I was up in Boston frequently. I could not imagine where I’d be without your love and support. I love you both very much.

- To Andrew and Emily. You are both truly stellar siblings, and I’m grateful for both of you, and that we will have one another going forward. Thank you for being yourselves, for being close friends and allies in this journey that none of us would have chosen.

- And lastly, Dad. Your dignity, your grace, and your steadfastness during undoubtedly the most painful time of your life was a true inspiration. In telling Mom’s story, your poise will always be something we cherish, and that we aspire to. Thank you so much.

I’ll close with a concept that my friend Liz introduced me to in grad school. She said it was from Buddhism though in my limited readings on Buddhism, I’ve never seen it. But regardless, this concept stipulates that everyone actually dies twice. The first time is when you shuffle off this earthly body. And the second time occurs when the last person who remembers you, passes away. And the reason is that everyone in your life, everyone you meet, carries with them the thoughts, the memories, and the influences that you had on their life.

And in Mom’s instance, everyone she taught – whether that’s me, Andrew, Emily, some 770-some school children, or any of us who knew her – will tell her story.

We are her story.

As I raise my own child, I’ll teach her to be curious. Independent. Grateful. And through all of it, to never lose her sass.

In other words, I’ll teach her how to live. And I can’t think of a better story to tell than that.