Several times during the last few weeks, I found myself thinking of Jiminy Cricket and Emily Dickinson.

Jiminy, those of a certain age will recall, used to sing “Books take you ‘cross the sea and down along a trail that never ends.” Emily, many will remember from high school, wrote “There is no Frigate like a Book, To take us Lands away.”

I recently returned from across the sea and lands away when I put down the 592-page historical novel Katherine, by Anya Seaton. This was one of those exceptional books that I just didn’t want to end. I felt like I was back in that time of Geoffrey Chaucer, of courtly love and arranged dynastic marriages, of treachery, adultery, and murder in the castles, of the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War, and of the history plays of William Shakespeare.

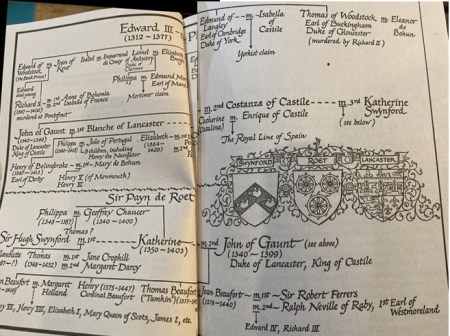

Katherine Swynford was mistress, love-of-life and eventual third wife to John of Gaunt, one of England’s greatest noblemen. Son of King Edward III and Duke of Lancaster, he never became King of England. But he would have been a much better monarch than his simpering nephew, Richard II, who succeeded Edward III on the throne and eventually screwed things up royally – pun intended.

Gaunt was smitten by Katherine’s beauty and regal presence almost from the time they met. He was married to the wealthy Blanche of Lancaster, with whom he had three children. Catherine, without dowry and second daughter of Payn de Roet, a knight who died at an early age, was married to another knight of slender means, Sir Hugh Swynford. She bore him two children.

Swynford was in Gaunt’s service and was a reliable and fierce warrior, but that’s about all he had going for him. He died under mysterious circumstances after returning from a military campaign. Gaunt’s first wife Blanche perished in the Black Death plague. Their spouses’ deaths would have freed John and Katherine to be together and make it official, you’d have thought, but that’s not what happened. He first married Queen Costanza of Castile, and he spent a good deal of time away in Spain trying to win more military victories and to become king of that realm. When he was in England, he eclipsed in strength and prestige the hapless King Richard, but he remained loyal until his death.

John’s loveless, political second marriage didn’t keep him and Katherine from having four children of their own. Somehow, that flame kept flickering and never went out. John found ways to share some of his wealth and keep her and their four bastard children financially solvent. It wasn’t that she was always there standing by him. They were apart and out of touch for long periods of time. She even contemplated suicide at one point. They finally married after his second wife died and spent three years together as husband and wife.

The author, Anya Seaton, took about a year and a half to write this book. She stayed true to historical fact and interpolated plausible though undocumented facts and motives where the record was lacking. She traveled through England and stood where her chronicled events took place. Her sources, among others, were Gaunt’s personal registers and the Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, highly detailed descriptions of the events of the Hundred Years’ War.

As she remarked in her journals, “I’m writing at least plausible history… I’m taking some liberties, etc.” Some of those liberties included imagining a deep-seated demon that plagued Gaunt from childhood and almost caused him to plunge England into a civil war. She has Katherine intervene and, through loving attention, quell the fires of his fury. As Seaton describes it, “Pretty psychiatric but I had to do it.”

Another couple of undocumented surmises by the author were her treatment of Geoffrey Chaucer and of Julian of Norwich, the revered religious leader, anchoress and author of the book of mystical devotions, Revelations of Divine Love.

Chaucer was actually Katherine’s brother-in-law, in a loveless marriage to her sister Philippa. He makes several brief appearances and inserts some wry and pithy observations; Seaton imagines that his Troilus and Criseyde was inspired by Katherine and John. She also had Swynford poisoned by a treacherous loyalist of Gaunt’s, although there is no evidence of that. Late in the book, Katherine, overwhelmed with guilt and on the brink of despair, is brought to Julian. Her experiences there, of course, are imagined by the author. Still, it is plausible – and I wanted to believe it was this way – that Julian relayed the following divine message to Katherine:

“It is truth that sin is the cause of all pain; sin is behovable – none the less all shall be well…Accuse not thyself overdone much, deeming that thy tribulation and thy woe is all thy fault; for I will not that thou be heavy or sorrowful indiscreetly.”

Yes, these are liberties taken by the author. But they work. As Seaton’s biographer Lucinda MacKethan points out about this book and Seaton’s next work, The Winthrop Woman, “Some readers have criticized the history of these works as too heavy, but for most, Anya’s great respect for what might be called the knowability of the worlds she was bringing to light in their greatest asset.”

I have to agree with that. As mentioned above, I felt like I was immersed in those worlds. No one can know what the people in them were actually thinking and feeling. And her description of the sack and burning of Savoy Palace during the Peasants’ Revolt was nothing short of terrifying. It certainly seemed true to history as far as I was concerned.

And for those aforementioned history plays of Shakespeare – particularly I Henry IV, Henry V, and Richard II – I finally learned who all those characters and parties to the conflicts were. They include, in addition to John of Gaunt, Henry Bolingbroke, Edward the Black Prince, Lord Harry Percy of Northumberland and his son Hotspur, Wat Tyler, Jack Straw, and the Dukes of Gloucester and York. They flit in and out of the history plays, and I always had a hard time remembering who the good guys were and who the bad guys were. Now I feel that I know where they all fit in the tumultuous history of the period.

Anyone who has read Shakespeare or dabbled in history has at least heard the name John of Gaunt. Like me, you probably regarded him as one of the big-time operators in a bygone age. And in that, you’d be right. But that’s the extent of it. Like me, you also would not have realized the profound impact he had on the history of the country of England. Nor, I daresay, had you ever heard of the formidable woman, the long-time mistress who at last became his wife, without whom John of Gaunt would have been just another member of the gone-and-forgotten noble class.

After Gaunt’s death, Richard II went off the rails and was succeeded by Bolingbroke, Gaunt’s son from his first marriage. He became Henry IV, and his son was the much mythologized Henry V. The Beauforts, who were the initially illegitimate children of Gaunt and Katherine, were the progenitors of Henry VII, the Tudor royal line, and the Stuart royal line. That includes, among others, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots, and James I. Katherine’s grandsons were Edward IV and Richard III.

Quite a legacy. As the final line of this wonderful book states, in quoting the witches in Macbeth, “Thou shalt get kings, though thou be none.”