Well, that headline is a bit of an exaggeration. But read on. There’s something to it.

According to “Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land” by Jacob Mikanowski, two towering figures dominated the cultural scene of that region in the idyllic decades before World War I destroyed that world: Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph I, and Anna Csillag.

That time, from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the outbreak of World War I, is fondly remembered as the Belle Epoque (or Beautiful Era). In America, it was dubbed the Gilded Age by Mark Twain. In Europe, there was peace and stability, and people had money to spend. And they spent a lot of money on the wondrous, but totally bogus, hair pomade made famous by Anna Csillag.

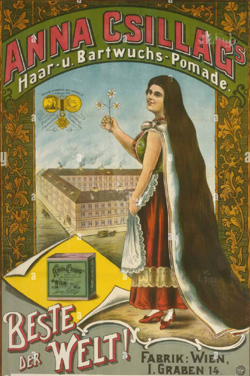

Mikanowski points out that Csillag’s image appeared in advertisements in every newspaper in Europe. The ads showed her in peasant garb, holding aloft three lilies, and nearly covered by her long and lustrous black hair, which “cascaded down her back like a wooly Niagara.”

How did she get that hair? The myth that her ads spun had her a poor young woman, nearly bald, and shunned by all those in her little village. But one day, she was working with chemicals and discovered a miraculous medicine that cured her baldness and became a hair-growing wonder drug. In her ads, printed in many languages, she wrote “I, Anna Csillag, possess an immense, 185-centimeter growth of Lorelei-like locks thanks to fourteen months spent using my specially formulated pomade.”

The men in her family got in on promoting the hair-growing too. The ads depicted them with “astounding pelts of lustrous black hair – fanlike beards stretching past their waists, and ropelike mustachios coiled around their trunks and midsections like so many boa constrictors.”

The ads appeared the papers of “Budapest, Krakow, Lodz, Vienna, Helsinki, Riga, and all points in between…the ads were so ubiquitous that they became part of the background hum or life in the Belle Epoque.” They also featured rapturous letters of endorsement by users.

The whole thing was a brilliantly executed con. Csillag – real name Stern – wasn’t born in “Karlowitz of Moravia,” as her ads claimed, but in Zalagerszeg, Hungary. She also sold a tea that was purportedly a miraculous shampoo, and a bar of soap that she plumped as “the best soap in the world.”

As she operated her business from Vienna and Budapest, the Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy come along to inspect. They found that the soap was just a red-brown toilet soap of inferior quality, and the tea was nothing but a common chamomile. As for the hair pomade, it was “nothing more than a mixture of fat and bergamot oil. It was white-gray in color, had the consistency of lard, and appeared grainy when spread out in a thin layer.”

Did that reality check matter? Nope. The stuff still sold. Or maybe the bureaucrats’ findings weren’t widely disseminated. And Mikanowski notes wryly, “with the benefit of hindsight we can say the imperial inspectors missed their mark. They evaluated a physical product, when the real miracle sold by Anna Csillag was her message. Repeated over and over again, it acquitted the force of a cryptic gospel or a prayer.”

Ah, the power of advertising. Anna would have made Don Draper and his coterie of Mad Men envious. But he did get the message. As Don he famously said in one episode, “What you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons.”

Someone else who was envious to the point of becoming enraged by Anna’s success in advertising was a penniless, struggling art student in Vienna. He spent hours poring over the ads, and he was especially fascinated by the letters of gratitude supposedly sent to Anna’s companies. He found that the letters were all fakes, and the supposed senders were dead.

The art student thought that he had found the key to a great mystery – the secret of propaganda. He ranted about its power, declaring to one friend “Propaganda, good propaganda, turns doubters into believers. Propaganda! We only need propaganda. Of stupid people there are always enough.”

The art student also wanted to turn his dormitory into an “advertising institute,” where the residents would all dedicate themselves to selling some product – perhaps a glass-strengthening paste – and promote it regardless of whether it worked. All they had to do, he claimed, was to repeat their message as often as possible, and, combined with a talent for oratory, they would attract all the customers they could want.

None of the guys in the dorm bought that scheme. One of them replied that they needed something worthwhile to sell, and that “after all, oratory on its own was useless.”

Rebuffed, the art student left school. But he wasn’t finished with the lessons he had learned from Anna Csillag and her fanciful stories. He found another dream to sell, another cryptic, diabolical gospel. He put Anna’s lessons to murderously effective use in his role of chancellor, and ultimately dictator, of the country of Germany.

From phony hair pomade to the brutal reality of a World War…now you know the rest of the story.